6 Foundational skills

Abstract

This chapter is designed to give readers the skills and knowledge necessary to start any of the walkthrough chapters. This chapter provides insights into key areas of using R, mental models for using R, and experience working with R using the RStudio Integrated Development Environment (IDE) through introductory applied examples. While this chapter covers introductory data manipulation in R, note that it is not a complete introduction to programming with R nor to using R for data science.

6.1 Topics emphasized

- Preparing your programming environment

- Using the pipe operator

- Using the assignment operator

6.2 Functions introduced

function()janitor::clean_names()janitor::remove_empty()c()dplyr::mutate()janitor::excel_numeric_to_date()dplyr::coalesce()dplyr::select()stats::filter()dplyr::filter()names()dplyr::glimpse()summary()dplyr::group_by()dplyr::count()dplyr::arrange()dplyr::desc()dplyr::rename()

6.3 Functions introduced in the appendix

read_csv()readxl::read_excel()haven::read_sav()googlesheets::gs_title()andgooglesheets::gs_read()

6.4 Chapter overview

This chapter is designed to give you the skills and knowledge necessary to get started in any of the walkthrough chapters.

The goal in this chapter is to give you insights into key areas of working with R, help you develop mental models for working with R, and ultimately to get you working with R using the RStudio Integrated Development Environment (IDE) through a series of introductory applied examples.

If you have not installed R and RStudio, please go through the steps outlined in Chapter 5 before beginning this one.

This chapter is not intended to be a full and complete introduction to programming with R nor to using R for data science. Please see Chapter 17 for some excellent resources that provide this kind of instruction.

This chapter includes the following topics:

- The foundational skills framework (understanding projects, functions, packages, and data)

- Using R’s “Help” documentation

- Working through new and unfamiliar content

- Getting started with a coding walkthrough

6.5 Foundational skills framework

No two data science projects are the same. Even so, this chapter includes a general framework for you to use during the walkthroughs in this book. The four core concepts of this framework are:

- Projects

- Functions

- Packages

- Data

6.6 Projects

One of the first steps of every workflow is setting up a “Project” within RStudio.

A Project is a home for all of the files, images, reports, and code used in a data analysis workflow.

To avoid confusion, we’ll capitalize “Project” when referring to a specific setup within RStudio.

Use Projects to create a self-contained folder for an analysis in R. If you want to share your Project with a colleague, they will not have to reset file paths in order to re-run your analysis.

Even if the only person you ever collaborate with is a future version of yourself, using a Project for each of your analyses will means that you can move the Project folder around on your computer and remain confident that the analysis will run in the future.

6.6.1 Setting up your project

To create a Project, open RStudio.

From RStudio, follow these steps:

- Click on “File”

- Select “New Project”

- Choose “New Directory”

- Click on “New Project”

- Enter your Project’s name in the box that says, “Directory name”. Choose a Project name like “DSIEUR” that helps you remember the content of the project. Avoid using spaces in your Project name. Instead, separate words with hyphens or underscore characters.

- Choose where to save your Project by clicking on “Browse” next to the box labeled “Create project as a subdirectory of:”.

- Click “Create Project”

At this point, you should have a Project that serves as a place to store .R scripts you create as you work through this text. For more practice, set up a couple more additional Projects by following the steps listed above. Within each Project, add and save .R scripts. Since this is just for practice, you can delete these Projects once you have the hang of the procedure.

It is not necessary to create a Project for your work but it is strongly recommend. When you use Projects in combination with the {here} package, you’ll have an easy-to-use workflow. For more on using Projects with the {here} package, read Bryan (2017)’s article(https://www.tidyverse.org/blog/2017/12/workflow-vs-script/). We will also explain more about the {here} package later in this text.

If you choose not to create a Project, you will still be able to navigate the walkthroughs in this text and carry out future analyses. However, be aware that at some point you may run into issues with how the files are structured on your computer.

You can always see where your computer is looking for your .R scripts by checking the working directory. To do that, run this code: getwd(). This will let you know what file path R is pointing towards. If needed, you can then change your working directory by running setwd() and providing your file path name as an argument. Note that when using this method, it becomes impossible for you or others to run your code on a different computer.

6.7 Functions

A function is a reusable piece of code that allows you to consistently repeat a programming task. Functions in R can be identified by a word followed by a set of parentheses, like so: word(). More often than not, the word is a verb, such as filter(), suggesting that you’re about to perform an action. Indeed, functions act like verbs: they tell R what to do with the data.

The word represents the name of the function, and the parentheses are where you provide arguments to a function when needed.

Many functions in R packages do not require you to pass them arguments. They use a set of default arguments unless you provide something different. There are not hard and fast rules about when a function needs an argument. However, if you are having trouble running your code, check the Help documentation to see if you can provide arguments that more clearly direct R what to do.

6.7.1 Writing Your Own Functions

As you work in R more and more, you may find yourself copying and pasting the same lines of code and then making small modifications. This is perfectly fine while you’re learning. But eventually, you’ll find that with large datasets this approach is inefficient and introduces the chance of errors.

Instead, consider using functions instead of copying and pasting code multiple times. A general premise in programming is DRY, or Don’t Repeat Yourself. Once you find yourself copying and pasting code for the third time, it’s time to write a function.

This chapter covers the very basics of writing a function. For more detailed guides, consider resources like the Creating Functions(https://swcarpentry.github.io/r-novice-inflammation/02-func-R/) tutorial from Software Carpentries(https://software-carpentry.org/).

In its most basic form, the template for writing a function is:

name_of_function <- function(argument_1, argument_2, argument_n){

code_that_does_something

code_that_does_something_else

}For example, if you wanted to create a function that adds two numbers together, you could write:

#' writing our function

#' we've named the function "addition"

#' and asked for two arguments, "number_1" and "number_2"

addition <- function(number_1, number_2) {

number_1 + number_2

}

#' using our function

#' below are 3 separate examples of utilizing our new function called "addition"

#' note that we provide each argument separated by commas

addition(number_1 = 3, number_2 = 1)

addition(0.921, 12.01)

addition(62, 34)Challenge Questions

For more practice, explore these questions:

- For our newly written function “addition”, what happens if we only provide one argument?

- What happens if we provide more than two arguments?

6.8 Packages

Packages are shareable collections of R code that contain functions, data, and documentation. Packages increase the functionality of R by providing access to additional functions to suit a variety of needs. While it is entirely possible to do your work in R without packages, it’s not recommend. There are a wealth of packages available that reduce the learning curve the time spent on analytical projects.

6.8.1 Installing and Loading a Package

6.8.1.1 Installing a package

In Chapter 5, you installed two packages, ({pak} and {dataedu}). In this section, you’ll learn more about installing and loading packages.

In order to access the functions within a package, you must first install the package on your computer. There are a collection of R packages hosted on the internet on the CRAN website: CRAN(https://cran.r-project.org/), the Comprehensive R Archive Network. These packages must meet certain quality standards, and are regularly tested.

When an R user wants to share their package with a broader audience, they can submit their package to CRAN. This process is beyond the scope of this book, but it’s important to point out that you—yes, you!—can create packages for yourself, to share with colleagues, or submit to CRAN. Most of the packages you’ll use in this book are available on CRAN, which means that we can install them using the install.packages() function.

If the package is on CRAN, install it by running the following code in the RStudio Console:

# Template for installing a package

# install.packages("package_name")

# Example of installing a package

install.packages("dplyr")Note that the name of the package needs to be inside quotation marks when using the install.packages() function.

You can run the install.packages() functions within an .R script If you choose to do this, make sure to comment out the lines of code that install packages after the packages are installed. This will save you time in the future since you don’t need to re-install packages each time you run a script.

If you do not want to write code for installing packages, you can also use the RStudio interface. Navigate to the “Packages” tab of the “Files” pane, click “Install”, and search for and install one or more packages.

Figure 6.1: Image of the Packages Pane, which is Found in the Bottom Right Corner of the RStudio IDE, along with the Files, Plots, Help, and Viewer Panes

6.8.1.2 Loading a package

Once a package is installed on your computer, you do not have to re-install it in order to use the functions in the package. However, you will need to load the package into your RStudio environment each time you open RStudio. Do this by using the library() function.

A package is like a book, a library is like a library; you use library() to check a package out of the library. -Hadley Wickham, Chief Scientist, RStudio

Loading a package into the R environment signals to R that you would like to use the functions available in that package. For example, load the package {dplyr} (Wickham et al., 2023) using the following code:

# template for loading a package

# library(package_name)

# example of loading a package

library(dplyr)Note that unlike installing a package, you do not need to put the package name inside quotation marks when using the library() function.

Sometimes you’ll see require() used instead of library(). The authors recommend using library(), as it forces R to load the package. With library(), RStudio will print out an error message if a package isn’t installed or isn’t working. require(), on the other hand, will not give errors in these cases.

6.8.2 How to find packages

As you begin your R learning journey, the bulk of the packages you will need to use are either already included when you install R or available on CRAN. CRAN Task Views (https://cran.r-project.org/web/views/) is one of the best resources for seeing what packages are available for your work. For more resources for R packages, try following the “#rstats” hashtag on Bluesky. Further, as R has grown in popularity, Google has gotten significantly better at returning R-related results.

6.8.3 Learning more about a package

Sometimes when you look up a package, you will be able to identify its function immediately. Other times, you may need to learn more about the package. Packages on CRAN come with “vignettes”, which are worked examples of the package’s functions. Access a package’s vignette(s) on CRAN Task Views.

Packages do not need to be on CRAN to be used by the public. Many are available directly from their developers via GitHub. Package authors may publish vignettes, blog posts, and tutorials about their packages. If you find yourself on GitHub looking at a package, more often than not, the README file will have information for getting started. At the time of publication, the {dataedu} package the authors created is available only through GitHub.

6.8.4 Installing the {dataedu} package

In Chapter 5, we provided the following code for installing the {dataedu} package. There are related packages that {dataedu} installs for you when you install the {dataedu} package. If you run into difficulties, a good place to start is re-installing the package to make sure you have the most updated version.

If you installed the {dataedu} package already, you can skip to the next section. Otherwise, run the following code. Please note that the {dataedu} package requires R version 3.6 or higher to run.

# Install pak

install.packages("pak", repos = "http://cran.us.r-project.org")

# Install the dataedu package

pak::pak("data-edu/dataedu")The {dataedu} package not available on CRAN yet. You’ll be installing it from GitHub. To do this, you first need to install the {pak} package.

The first function, install.packages("pak", repos = "http://cran.us.r-project.org"), has two arguments, "pak" and repos = "http://cran.us.r-project.org". The first argument, "pak", is the name of the package you’re installing. The second argument, repos = "http://cran.us.r-project.org", tells R the URL of the repository to use. The repository is the place where a package’s code is stored.

The second function, pak::pak("data-edu/dataedu"), has one argument, "data-edu/dataedu". It looks different from the first function. This line of code tells R to go to the {pak} package and find the pak() function.

The pak() function tells R to go to a GitHub repository to get the code for the {dataedu} package. You can see the repository for the {dataedu} package on GitHub(https://github.com/data-edu/dataedu).

6.8.5 Loading the {dataedu} package

Now that you’ve installed the {dataedu} package, load it using library(). You can create an .R script in your Project to load and explore the {dataedu} package. We’ll load the {dataedu} package by running the following code in an .R script:

When working with packages, you don’t include the install.packages() function in your .R scripts. But you do include library() functions. Doing so ensures you and others load the correct packages at the start of the data analysis.

6.8.6 Using the {dataedu} package

There are some basic functions in the {dataedu} package that are helpful to know.

6.8.6.1 Installing the packages used throughout this book

Type and run dataedu::install_dataedu() in your Console to install the packages used in this book.

If you prefer to install the required packages one by one, run the following code in the RStudio Console: dataedu::dataedu_packages.

This will print list of the packages included in the {dataedu} package. You can then install each package individually using install.packages("package_name").

If encounter errors, please reach out to us! You can file an issue on GitHub, or email us at authors@datascienceineducation.com (authors@datascienceineducation.com)

6.8.6.2 Accessing the datasets used in this book

All of the datasets used in this book are available through the {dataedu} package and through downloadable .csv files stored in the data folder within our GitHub repository(https://github.com/data-edu/dataedu).

You can load any of the data files using the following code: dataedu::dataset_name.

You’ll practice doing this in a later section of this chapter. If you want to try it out now, the names of the available datasets are:

- course_data

- course_minutes

- district_merged_df

- district_tidy_df

- longitudinal_data

- ma_data_init

- pre_survey

- sci_mo_processed

- sci_mo_with_text

- tt_tweets

6.8.7 The relationship between packages and functions

Packages are a collection of functions and most are designed for a specific dataset, field, or set of tasks. Functions are individual components within a package and are what you use to work with data.

To put it another way, an R user might write a series of functions they use repeatedly in a variety of projects. Instead of re-writing or copying and pasting the functions each time the user needs them, they can collect the individual functions inside a package. Then they can load the package and included functions using a single line of code.

6.9 Data

Throughout this book, you’ll see data accessed in different ways. For example, users can pull data directly from a website or load the data from a .csv or .xls file.

The datasets explored in this book are included as .rda files in the {dataedu} package (R. Estrellado et al., 2025). There are additional resources for loading data from Excel, SAV, and Google Sheets in Appendix A.

It is also possible to connect directly to a database using R. We do not cover that text in this text. For more information about this method, consider starting with the Best Practices in Working with Databases (https://solutions.posit.co/connections/db/) resource from Posit.

6.10 Help documentation

Very few know everything there is to know about R. It’s common to need to look things up when solving problems using R. Thankfully, R includes excellent built-in resources for you.

Within RStudio, access the “Help” documentation by using ? or ?? in the Console. For example, if you wanted to look up information on the data() function, type ?data or ?data() next to the carat (>) in the Console, and hit Enter.

Try this now. You should see the Help panel in your RStudio environment display documentation on the data() function.

This works because the data() function is part “base R”—it’s included with R when you first install it. But this also works for packages outside of base R.

The Help documentation is a great first step when you’ve got a question about R. The next section provides you with more tips for problem solving while you do data analysis.

6.11 Steps for working through unfamiliar R content

Great educators know how to ask great questions. Asking the learners in your classroom the right questions at the right time facilitates understanding, uncovers misconceptions, and helps you understand if they’re grasping the concepts.

However, when you’re learning on your own, you are both the educator and the learner. You must know how and when to ask yourself questions. You must also answer your questions, evaluate your answers, and guide your learning path as you progress.

This section gives you steps to use as you encounter new R content. You’ll use the example of encountering a function for the first time, but you can use these steps in a variety of situations while learning R.

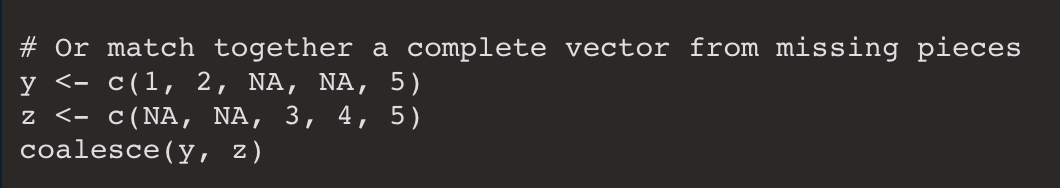

Imagine that you’ve been reading through a tutorial and have come across the coalesce() function in the vignette for the {janitor} function(https://github.com/sfirke/janitor):

library(tidyverse)

library(janitor)

roster <- roster_raw %>%

clean_names() %>%

remove_empty(c("rows", "cols")) %>%

mutate(hire_date = excel_numeric_to_date(hire_date),

cert = coalesce(certification, certification_1)) %>%

select(-certification, -certification_1)6.11.1 Activate prior knowledge

To activate prior knowledge, take a moment to think through the following questions:

- What does the word “coalesce” mean?

- Have you ever seen the

coalesce()function before? If so, in what context?

6.11.2 Look for context clues

Read a couple of lines of code both above and below where the coalesce() function appears—are there clues about what this function might do?

6.11.3 Check the help documentation

What information is available in the Help documentation? Are there examples from the Help documentation that are similar to the code you’re reviewing? For example, this seems related:

Figure 6.2: Example from the coalesce() Help Documentation

6.11.4 Find the limits

Work through examples in the Help documentation or examples you’ve discovered online and test the limits.

Testing the limits is a way of understanding the code by seeing how it handles different situations. Testing limits helps you recognize patterns, develop a hypotheses about what code does, and test whether that hypothesis is true.

Try editing code to answer questions that help you learn. Examples include:

- What happens if you substitute obviously larger or smaller values?

- What happens if you substitute different data types?

- What happens if you introduce

NAvalues? - Is the order of values important?

6.11.5 Test your understanding through communication

Take a moment to think through whether you could explain what you’ve learned to someone else. Imagine the questions someone would ask of you and try to answer them. If you can’t, dig deeper into the documentation, online forums, and conversations with other R users.

You won’t always have the time to follow all these steps for each unfamiliar piece of R content you encounter. But we hope this provides you with a starting framework for furthering your understanding.

6.12 Bringing it all together: getting started coding walkthrough

In this section, you’ll take everything you’ve learned so far and apply it to some introductory code. This code isn’t a comprehensive data analysis, but it does use exploratory data analysis techniques.

Before beginning this section, you’ll need to have installed the {dataedu} package and that you have also run dataedu::install_dataedu() to install the associated packages. If you have not done this yet, please do so before continuing.

6.12.1 Creating a project and an .R script

If you haven’t already, set up a Project in RStudio and create a new .R script, as described earlier in this chapter. Save your .R script as “chapter_6_walkthrough” or another similar name. Run the following code in the RStudio Console to install the {skimr} package, which you’ll use to create summary statistics.

Next, type out and run the following lines of code in your .R script, one by one, and notice what happens in the Console after you run each line.

Reflect on these questions to further your learning:

- What do you think running the above lines of code accomplished?

- How do you know?

6.12.1.1 Function Conflicts between Packages

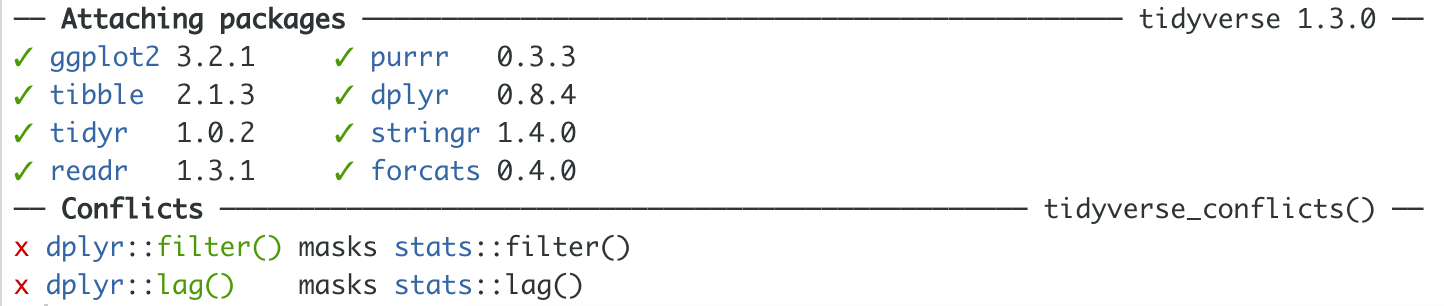

In your Console, you may have noticed the following message:

Figure 6.3: List of Attached Packages and Associated Conflicts when Loading the tidyverse

This isn’t an error. It’s important information that for you consider ahead of your analysis. When we first open R (via RStudio) we are working with base R—that is, everything that comes with R and a handful of pre-installed packages.

These are packages and functions that exist in R without loading additional packages.

If you would like to see what functions are available to you in base R, you can run library(help = "base") in the Console.

If you would like to see the packages that came pre-installed with R, you can run installed.packages()[ installed.packages()[,"Priority"] %in% "base", c("Package", "Priority")] in the Console.

Additionally, if you would like to see a list of all of the packages that have been installed (both pre-installed with base R as well as those that you have installed), you can run rownames(installed.packages()) in the Console.

Because of the many packages that have been created for use in R, it’s not uncommon for packages to have functions with the same name.

This message tells you that if you use the filter() function, R will use the filter() function from the {dplyr} package (a package in the {tidyverse}) rather than the filter() function from the {stats} package (a package in base R). R gives precedence to the most recently loaded package.

Take a moment to use the Help documentation to explore how these two functions differ.

If R gives precedence to the most recently loaded package, you may be wondering how to use the filter() function from the {stats} package and the filter() function from the {dplyr} package in the same R session.

One solution is to reload the library you want to use each time you want to change the package you’re using the filter() function from. However, this can be tricky for several reasons:

- It’s best practice to keep your

library()calls at the very top of your R script, so reloading a package usinglibrary()throughout your script clutters things and can cause you headaches down the road. - If you scroll to the top of your script and reload the packages as you need them, it becomes difficult to keep track of which one you recently loaded.

Instead, there’s an easier way to handle this kind of problem. When you have conflicting function names from different packages, tell R which package you’d like to pull a function from by using ::.

Using the example of the filter() function above, coupled with the examples in the Help documentation, specify which package to pull the filter() function from using ::, as outlined below.

Note: we haven’t covered what any of this code does yet, but see what you can learn from running the code and using the Help documentation

6.12.2 Loading data from {dataedu} into our R Environment

In this section, you’ll learn how to load a dataset from the {dataedu} package into the R Environment. You’ll assign that dataset to an object so you can use it in downstream analyses.

In Appendix A, we show how to directly access data from other sources: Excel, SPSS (via .SAV files), and Google Sheets. For now, you will be loading datasets that are stored in the {dataedu} package.

Type out and run the following lines of code one by one, and notice what happens in the Console after you run each line.

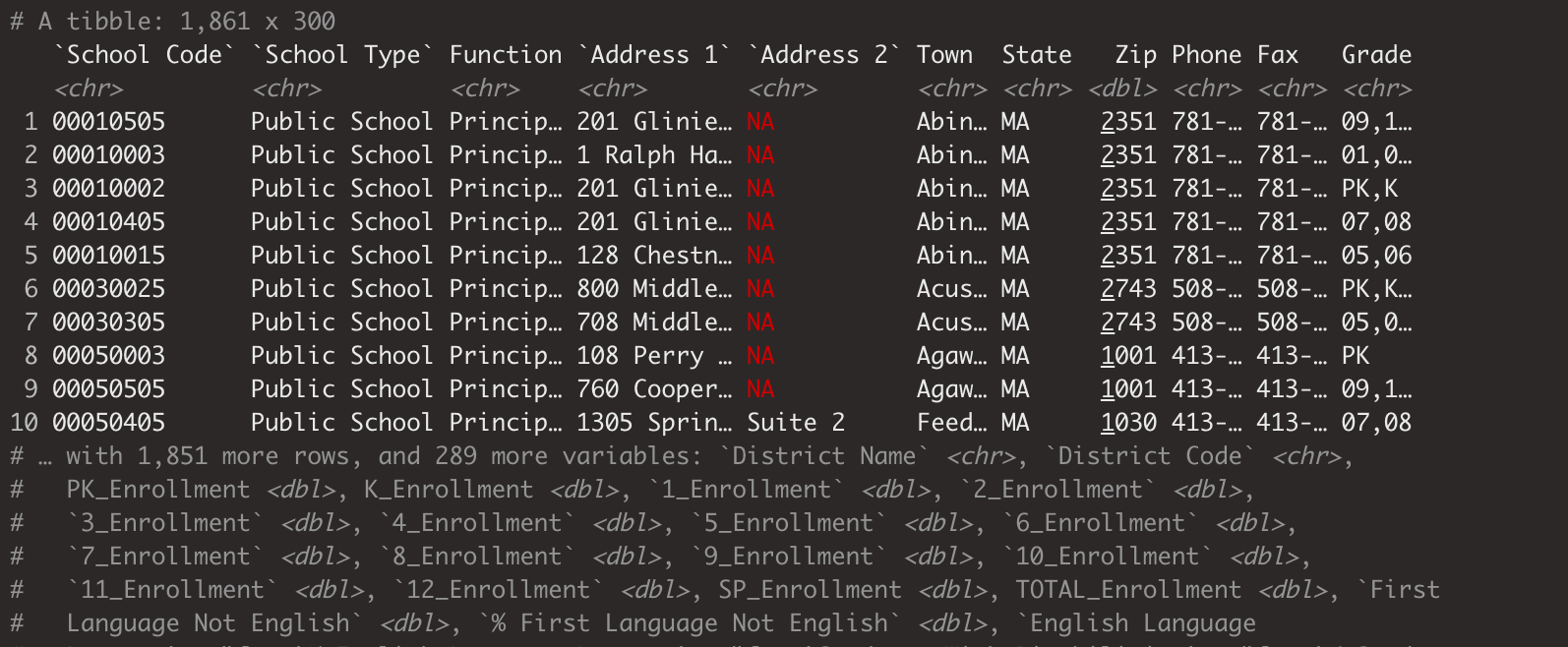

Each of the three code examples above differs slightly, but two lines of code do almost exactly the same thing. The first example loads the data into our R environment, but not in a format that’s immediately useful. The second and third lines of code load the data and assign it to a new object,ma_data and ma_data_init, respectively.

In our Environment pane, you can see the data that’s been loaded in R. You can click on the table icon on the far right of the row in the Environment pane to get an interactive table. In this case, the dataset is rather large, so RStudio may lag slightly as you open the table.

Figure 6.4: Loading the ma_data Dataset

6.12.2.1 The assignment operator

The second and third examples in the code chunk above are how you’ll most commonly see data loaded and assigned to a variable. When saving something to a variable, you’ll do so using an “assignment operator.” In R, commonly used assignment operators are a left- or a right-facing arrow (<- or ->).

Writing the name of your variable followed by a left-facing arrow is a common convention used in R. Intuitively, the right-facing arrow may make more sense for those of us who work in languages that read left to right. The code essentially says “Take this chunk of code and save it to this variable name”. Regardless of which option you choose, both accomplish the same thing.

6.12.3 Exploring data and common errors

This next chunk of code uses functions to explore the data. It also introduces common errors when writing R code.

Type out and run the following lines of code one by one, and notice what happens in the Console after you run each line. If you’d like, practice commenting your code by noting what happens with each line of code that you run.

Note: we intentionally included errors in this and subsequent code chunks to help you learn about them.

# You probably wrote these 3 library() lines in your R script file earlier.

# If you have not yet run them, you will need to run these three lines before running the rest of the chunk.

library(tidyverse)

library(dataedu)

library(skimr)

library(janitor)

# Exploring and manipulating your data

names(ma_data_init)

glimpse(ma_dat_init)

glimpse(ma_data_init)

summary(ma_data_init)

glimpse(ma_data_init$Town)

summary(ma_data_init$Town)

glimpse(ma_data_init$AP_Test Takers)

glimpse(ma_data_init$`AP_Test Takers`)

summary(ma_data_init$`AP_Test Takers`)Reflect on these questions to further your learning:

What differences do you see between each line of code?

How do the results in the the Console change with each line of code you run?

6.12.3.1 Common errors: typos, spaces, and parentheses

There were two lines of code that resulted in errors and both were due to one of the most common sources of error in programming—typos!

The first was glimpse(ma_dat_init).

This might be a tricky error to spot because at first glance it doesn’t look like anything is wrong. However, there’s a missing “a” in “data”, which caused the error.

Remember that R will do exactly what you tell it to do. If you want to run a function on a dataset, R will only run the functions available in its environment. Looking at our Environment pane, you’ll see there is no dataset called ma_dat_init, which is what R is trying to tell us with its error message of Error: object 'ma_dat_init' not found.

The second error was with glimpse(ma_data_init$AP_Test Takers). What do you think the error is here?

R is unhappy with the space in the argument, and it doesn’t know how to read the code. There are a few things you can do to get around this. First, you can make sure that data column names never have spaces in them. This is not always within your control unless you are the creator of the datasets you use. Second, you can use R to manipulate the column names after you import the data and before you start exploring it. Third, you can leave the column names as they are but use single backticks (`) to surround the column header with spaces in it.

Note: the single backtick key is usually in the top-left of your keyboard. It’s common to try and use a set of single quotation marks (’ ’) instead of the actual backticks, but they don’t work the same way.

The $ operator

There are many ways to isolate and explore a single variable in your dataset. In the set of examples above, you used the $ symbol. The pattern for using the $ symbol is name_of_dataset$variable_in_dataset. You can see how this works in the last three lines of code in the code chunk above: it is a way of subsetting.

It’s important that the spelling, punctuation, and capitalization you use in your code match what’s in your dataset; otherwise, R will tell you that it can’t find what you’ve asked it to.

6.12.4 Exploring data with the pipe operator

This next code chunk introduces an operator known as the pipe (%>%). The pipe operator allows you to link functions together so you can run the data through multiple sequential functions. The keyboard shortcut for typing the pipe operator is Ctrl + Shift + M.

Note: You can find additional keyboard shortcuts for RStudio by going to “Help” in the top bar and then selecting “Keyboard Shortcuts Help”.

Type out and run the following lines of code one by one, and notice what happens in the Console after you run each line. You will run into an error message in one of the code chunks, but just try to understand what it means and continue. We will explain this code below.

ma_data_init %>%

group_by(District Name) %>%

count()

ma_data_init %>%

group_by(`District Name`) %>%

count()

ma_data_init %>%

group_by(`District Name`) %>%

count() %>%

filter(n > 10)

ma_data_init %>%

group_by(`District Name`) %>%

count() %>%

filter(n > 10) %>%

arrange(desc(n))Before a fuller explanation of the code below, let’s discuss the error. You got an error due to an “unexpected symbol”. Like early examples, this error is caused by the space in the variable name. In the code chunk you just ran, you can enclose District Name in backticks to resolve this error.

6.12.4.1 Reading code

When you encounter new-to-you code, it’s helpful to read the code out loud and develop a hypothesis about what it’s meant to accomplish. Doing this helps you understand the code better. It also helps you spot errors more quickly.

The way that you would read the last chunk of code you ran is:

Take the

ma_data_initdataset and then group it byDistrict Nameand then count the number of schools in a district and then filter for Districts with more than 10 schools and then arrange the list of Districts and the number of schools in each District in descending order, based on the number of schools.

That’s a mouthful! Every time you see the pipe, you’d say “and then”. This is because you’re starting with the dataset, ma_data_init, and then doing one thing after another to it.

Because you’re using the pipe operator between each function, R knows that all of the functions are being applied to the ma_data_init dataset. You don’t need to refer to the ma_data_init data in each new line of code. Linking functions together using the pipe operator is commonly referred to as “chaining together functions”.

6.12.4.2 The pipe operator

The pipe operator %>% sometimes throws R learners for a loop until something clicks for them. Then they decide they either love it or hate it.

We use the pipe operator throughout this text because we also rely heavily on the use of the {tidyverse}, which is a collection of packages designed for data science workflows.

Note: as you progress in your R learning journey you may find you need to move well beyond the tidyverse for accomplishing your analytic goals—and that’s OK. We like the tidyverse for teaching and learning because it relies on the same syntax across packages. So as you learn how to use functions within one tidyverse package, you’re learning the syntax for functions in other tidyverse packages.

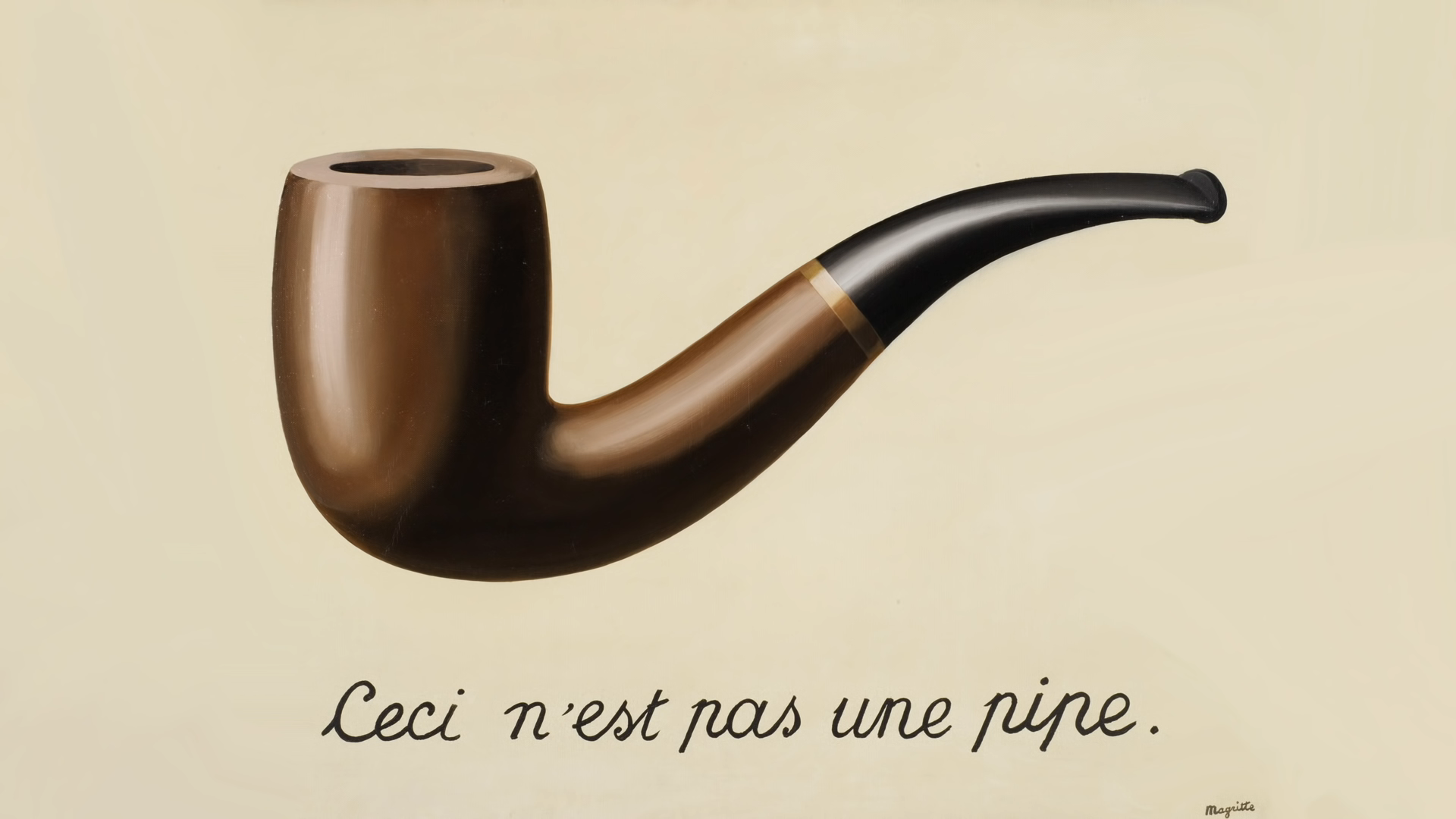

Here’s some fun history about the pipe operator and its package: The pipe operator first appeared in the {magrittr} package and is a play on a famous painting by the artist Magritte, who painted The Treachery of Images. In these images, he would paint an object, such as a pipe, and accompany it with the text “ceci n’est pas une pipe”, which is French for “this is not a pipe”.

Figure 6.5: The Treachery of Images by Magritte

It’s common in the R programming world to name a package by choosing a word that represents what the package does or what it’s for, then capitalizing the letter R if it appears in the package name or adding an R to the end of the package ({dplyr}, {tidyr}, {stringr}, and even {purrr}).

In this case, the author of the {magrittr} package created a series of pipe operators and then collected them in a package named after the artist Magritte.

R version 4.1.0 introduced the native pipe operator, |>. Like the {magrittr} pipe, it passes an object to a function so that you can chain a sequence of operations together. For straightforward use cases, both pipes behave similarly. However, you may run into differences in more complex scenarios. The code examples in this book use the {magrittr} pipe because it is tightly integrated with the tidyverse.

6.12.5 Exploring assignment vs. equality

You’ve learned a couple of operators already: namely the assignment operator (<- or ->) and the pipe operator (%>%). Now you’ll learn about = and ==.

Read through the code below before typing or running anything in R. Try to guess what is happening in each code chunk by writing a sentence for each line of code so that you have a small paragraph for each chunk. Once you’ve done that, type and run the following lines of code one by one and notice what happens in the Console after you run each line.

ma_data_init %>%

group_by(`District Name`) %>%

count() %>%

filter(n = 10)

ma_data_init %>%

group_by(`District Name`) %>%

count() %>%

filter(n == 10)

ma_data_init %>%

rename(district_name = `District Name`,

grade = Grade) %>%

select(district_name, grade)6.12.5.1 The difference between = and ==

Earlier you learned about using a left- or right-facing arrow to assign values or code to a variable. You can also use an equals sign (=) to accomplish the same thing. When R encounters an equal sign (=) it creates an object by assigning a value to a variable. So when you used filter(n = 10) in the first example in the code chunk above, R didn’t know how to filter something being assigned to a variable and told us so with an error message.

When determining whether or not values are equal, use a double equals sign (==), as you did in filter(n == 10). When R sees a double equals sign (==) it evaluates whether or not the value on the left is equivalent to the value on the right.

6.12.6 Basics of object and variable names

Naming things is important! The more you use R, the more you’ll develop a sense of how you prefer to name things, either as an organization or an individual programmer. However, there are some hard and fast rules that R has about naming things. Using the code chunk below, try saving the ma_data_init dataset into few different object names. You’ll be using the clean_names() function from the {janitor} package, which you already loaded into your environment earlier using the library(janitor) function. Type out and run the following lines of code one by one, and notice what happens in the Console after you run each line.

ma data <-

ma_data_init %>%

clean_names()

01_ma_data <-

ma_data_init %>%

clean_names()

$_ma_data <-

ma_data_init %>%

clean_names()

ma_data_01 <-

ma_data_init %>%

clean_names()

MA_data_02 <-

ma_data_init %>%

clean_names()As you saw in the above examples, R doesn’t like names that start with a number or symbol. In addition, R also throws an error when you give it a name with a space in it.

As such, variable names in R must start with a letter, though it doesn’t matter if the letter is capitalized or in lower case.

6.13 Conclusion

It’s impossible to cover everything you can do with R in a single book chapter, but we hope this chapter gives you a foundation from which to explore subsequent chapters and other R resources. Appendix A1 extends the techniques introduced in the foundational skills chapter—particularly, reading data from various sources (not only CSV files but also SAV, XLSX files, and spreadsheets from Google Sheets).

In this chapter, you learned about Projects, functions, packages, and data. We hope you feel prepared to tackle the subsequent walkthrough chapters.

We note that we will have a few other appendices like this one to expand on the content in the walkthrough chapters.↩︎