8 Walkthrough 2: Approaching gradebook data from a data science perspective

Abstract

This chapter explores cleaning, tidying, visualizing, and modeling classroom gradebook data. Data scientists in education work with a variety of data sources, including learning management systems (LMS). Using gradebook data, this chapter explores developing hypotheses about relationships between student work and formative assessments. It walks through running correlations and linear regressions in R. The chapter explains the importance of responsibly reporting analysis results to inform decision making. Data science techniques in this chapter include reading data from Excel, cleaning data, creating new variables, visualizing data, checking model assumptions, and reviewing results.

8.3 Vocabulary

- correlation

- directory

- environment

- factor level

- linear model

- linearity

- missing values/NA

- outliers

- string

8.4 Chapter overview

Whereas Walkthrough 1 in Chapter 7 focused on the education data science pipeline in the context of an online science class, this walkthrough further explores the ubiquitous but not-often-analyzed classroom gradebook dataset. You will use data science tools and techniques, including correlations and linear models.

This walkthrough provides another example of a commonly used education dataset. But we encourage you to imagine how the techniques from this walkthrough can be applied to other areas. There are a variety of data sources to explore in the education field. Student assessment scores can be analyzed for progress towards goals. The text from a teacher’s written classroom observation notes about a learner’s in-class behavior or emotional status can be analyzed for trends. Exportable data from learning software or platforms in the K–12 education space can be analyzed for patterns over time.

8.4.1 Background

This walkthrough goes through a series of analyses using the data science framework. The first analysis centers around a common K–12 classroom tool: the gradebook. While gradebook data is common in education, it is sometimes ignored in favor of other sources, like data collected by researchers or data from state-wide tests. Nevertheless, it represents an important untapped data source.

8.4.2 Data sources

In this walkthrough, you’ll use an Excel gradebook template, Assessment Types Points (https://web.mit.edu/jabbott/www/excelgradetracker.html), coupled with simulated student data. On your first pass through this section, try using our simulated dataset found in this book’s “data” folder.

You can access the “data” folder by navigating to the book’s GitHub repository(https://github.com/data-edu/data-science-in-education) and clicking on the “data” folder. From inside the “data” folder, click on “gradebooks”. The file with simulated gradebook data is named ExcelGradeBook.xlsx. When you click on the file name, you will see two buttons: one that says “Download” and another that says “History”. Click on the “Download” button to download the ExcelGradeBook.xlsx file to your computer.

8.5 Load packages

Begin by loading the libraries used in this analysis. Among others, you’ll use the {tidyverse} package used in Walkthrough 1 in Chapter 7. You’ll also use the {readxl} package to read and import Excel spreadsheets, which are very common file types in the education field. Finally, you’ll use the {janitor} package (Firke, 2024), which provides functions for cleaning and preparing data.

Make sure you have installed the packages in R on your computer before starting. For more on how to do this, see the “Packages” section of the “Foundational Skills” chapter.

The libraries must be loaded each time we start a new project:

8.6 Import data

In Appendix A, it’s recommended to use .csv files, or comma-separated values files, when working with datasets in R. This is because .csv files, with the .csv file extension, are common in the data science world. They are “plain text”—they tend to be faster when imported, do not have formatting, and are generally easier to deal with than Excel files.

However, data won’t always come in your preferred file format. Fortunately, R can import a variety of data file types. In this walkthrough, you’ll import an Excel file. You’re likely to encounter these file types, with the .xlsx or .xls extensions, in the K–12 education world.

Next, you’ll explore two ways to import the gradebook dataset. The first uses a file path and the second uses the here() function from the {here} package.

8.6.1 Import using a file path

This code uses the read_excel() function of the {readxl} package to find and read data in the desired file. Note the file path that read_excel() uses to find the simulated dataset named ExcelGradeBook.xlsx, which sits in a folder on your computer where you downloaded it. The function getwd() helps you locate your current working directory. This location is where R is currently working with files.

For example, an R user on Linux or Mac might see their working directory as: /home/username/Desktop. A Windows user might see their working directory as: C:\Users\Username\Desktop.

From this location, go deeper into files to find the desired file. For example, if you downloaded the book repository (https://github.com/data-edu/data-science-in-education) from Github to your Desktop, the path to the Excel file might look like one of these:

/home/username/Desktop/data-science-in-education/data/gradebooks/ExcelGradeBook.xlsx(on Linux & Mac)C:\Users\Username\Desktop\data-science-in-education\data\gradebooks\ExcelGradeBook.xlsx(on Windows)

After locating the sample Excel file, use the code below to run the function read_excel(), which reads and saves the data from ExcelGradeBook.xlsx to an object called ExcelGradeBook.

Note the two arguments specified in this code: sheet = 1 and skip = 10. This Excel file is similar to one you may encounter in real life, including extra features you don’t need for your analysis. Specifically, this file has three different sheets and the first ten rows contain information you don’t need. Thus, sheet = 1 tells read_excel() to read only the first sheet in the file and disregard the rest. Then, skip = 10 tells read_excel() to skip the first 10 rows of the sheet and start reading from row 11. This is where the column headers and data actually start inside the Excel file.

Try this code, but remember to replace path/to/file.xlsx with the correct path from your computer.

8.6.2 Import using here()

Whenever possible, use here() from the {here} package because it conveniently guesses the correct file path based on the working directory. In your working directory, place the ExcelGradeBook.xlsx file in a folder called “gradebooks”. Then place the “gradebooks” folder in a folder called “data”. The last step is to make sure your new “data” folder and all its contents are in your working directory. Following those steps, use this code to read the data in:

# Use readxl package to read and import file and assign it a name

ExcelGradeBook <-

read_excel(

here("data", "gradebooks", "ExcelGradeBook.xlsx"),

sheet = 1,

skip = 10

)The ExcelGradeBook file has been imported into RStudio. Next, assign the data frame to a new name using the code below. Renaming cumbersome file names improves the readability of the code and makes it easier for the user to call on the dataset later in the analysis.

Your environment now has two versions of the dataset. There is ExcelGradeBook, which is the original dataset you imported. There is also gradebook, which is a copy of ExcelGradeBook.

As you progress through this section, you will work primarily with the gradebook version. If at any point you’d like to start with a fresh gradebook dataset, you can do so by running gradebook <- ExcelGradeBook again. This will overwrite any changes in the gradebook data frame with the originally imported ExcelGradeBook data frame.

Now that you’ve tried two ways to import the dataset, you will now begin processing the data.

8.7 Process data

8.7.1 Tidy data

This walkthrough uses an Excel data file because you’re likely to encounter this format in your work. Moreover, the messy state of this file mirrors what you might be asked to use in your everyday work. The Excel file contains more than one sheet, has rows you won’t need, and uses column names that have spaces between words. All these things make the data tough to work with.

It’s possible to manually change the file before importing it. However, if you clean the file outside of R, there’s no record of the procedure you used. You or a coworker would need to rely on memory or backwards engineering to clean it in the future. On the other hand, when you clean the original data in R, you can recreate all the cleaning steps necessary for your analysis.

In this section, you’ll start your work with the column names. First, you’ll modify the column names of the gradebook data frame to replace spaces an underscore. In R, spaces in column names can present challenges later on in your analysis.

Second, you’ll make the column names of the data easy to use and understand. The original dataset has column names with uppercase letters and spaces. You’ll use the {janitor} package to change them to a more usable format.

8.7.2 About {janitor}

The {janitor} package is a great resource for anybody who works with data, particularly for data scientists in education. Created by Sam Firke, the Analytics Director of The New Teacher Project, it is a package designed with education data in mind.

{janitor} has handy functions to clean and tabulate data. Examples include:

clean_names(), which takes messy column names that have periods, capitalized letters, spaces, etc., and changes them into an R-friendly formatget_dupes(), which identifies duplicate recordstabyl(), which tabulates data in adata.frameformat. In this format, data can be “adorned” with theadorn_functions to add total rows, percentages, and other dressings

Start by looking at the original column names. The output will be long, so look at the first ten by using head().

## [1] "Class" "Name" "Race" "Gender"

## [5] "Age" "Repeated Grades"You can look at the full output by removing the call to head().

Now look at the cleaned names:

## [1] "class" "name" "race" "gender"

## [5] "age" "repeated_grades"Review the gradebook data frame again. It shows 25 students and their individual values in columns like projects or formative_assessments.

The data frame looks cleaner but there are still some things to remove. For example, there are rows without names in them. Also, there are entire columns that are unused and contain no data, like gender. These are called missing values and are denoted by NA. Since our simulated classroom only has 25 learners and doesn’t use all the columns for demographic information, you can remove these to tidy the dataset even more.

Remove the extra columns and rows that have no data using the remove_empty() function:

# Removing rows with nothing but missing data

gradebook <-

gradebook %>%

remove_empty(c("rows", "cols"))Now that you’ve removed the empty rows and columns, notice two columns, absent and late. It looks like someone started inputting data and then stopped. These two columns weren’t removed by the last chunk of code because they contain data. But since the absent and late columns aren’t complete you can remove it from the data frame for the purposes of this analysis.

In the “Foundational Skills” chapter, you learned about the select() function, which tells R what columns you want to keep. Use that again here, but this time use negative signs to remove absent and late.

# Remove a targeted column because we don't use absent and late at this school.

gradebook <-

gradebook %>%

select(-absent, -late)At last,you’ve turned the Excel sheet into a useful data frame. Inspect it once more to see the difference.

8.7.3 Create new variables and further process the data

R users transform data so it’s easier to visualize and analyze. Creating new variables and grouping data are examples of data transformation. The following code chunk creates a new data frame named classwork_df, then selects variables from the gradebook dataset using select(), and finally “gathers” all the homework data into new columns.

select() is very powerful, particularly when combined with other functions like those found in the package {stringr}. The {stringr} package is contained within the {tidyverse} meta-package.

Here, we’ll use the function contains() from {stringr} to tell R to select columns that contain specific text. The function will search for any column with the string classwork_. The underscore makes sure the variables from classwork_1 all the way to classwork_17 are selected.

pivot_longer() transforms the dataset into tidy data, where each variable forms a column, each observation forms a row, and each type of observational unit forms a table.

Note also that scores are in character format. We use mutate() to transform them to numeric.

# Creates new data frame, selects desired variables from gradebook, and gathers all classwork scores into key/value pairs

classwork_df <-

gradebook %>%

select(

name,

running_average,

letter_grade,

homeworks,

classworks,

formative_assessments,

projects,

summative_assessments,

contains("classwork_")) %>%

mutate_at(vars(contains("classwork_")), list(~ as.numeric(.))) %>%

pivot_longer(

cols = contains("classwork_"),

names_to = "classwork_number",

values_to = "score"

)View the new data frame and notice which columns were selected using the code above. Also, note how all the classwork scores were gathered under the new columns classwork_number and score.

8.8 Analysis

8.8.1 Visualize data

Visual representations of data are more human friendly than looking at numbers alone. This next line of code shows a summary of the data by each column, similar to the work you did in Walkthrough 1.

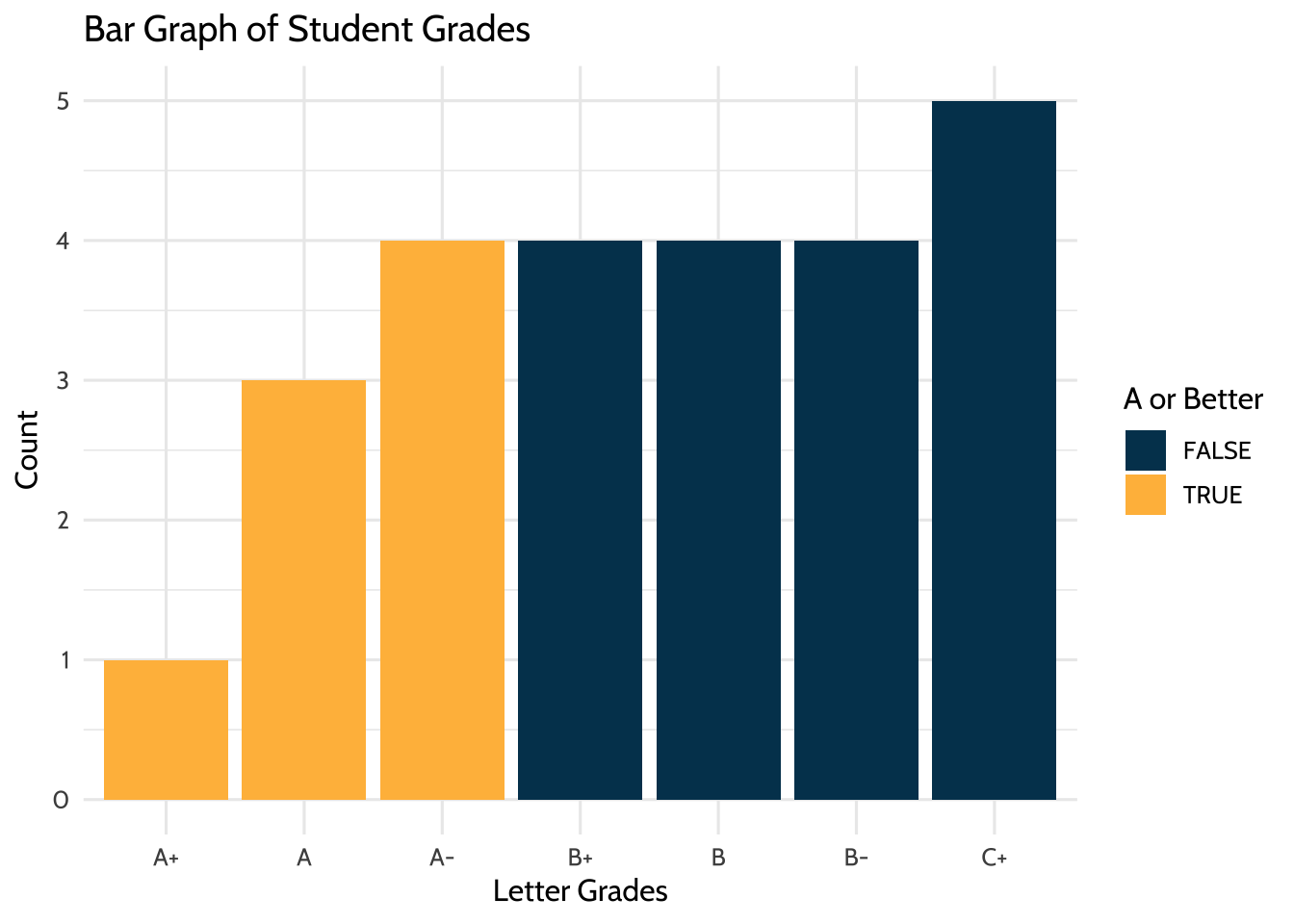

But R can do more than print numbers to a screen. In this section, you’ll use the {ggplot2} package to graph the data. This code uses {ggplot2} to organize categorical variables into a bar graph. Here, you can see the variable letter_grade is plotted on the x-axis and counts of each letter grade are on the y-axis.

letter_grades has “factor levels”, which give the categorical variables a predefined order. If you plotted this graph using the code below without defining the order of the letter grades, {ggplot2} would default to the lexicographic ordering of factors on the horizontal axis (i.e., A, A-, A+, B, B-, B+, etc.).

It is more useful to have the traditional order of grades, with A+ being the highest (and furthest left). You do this by using mutate(), noting the variable you want to order (letter_grade, in this case) and the factor levels (the grades on a scale from A+ to C+, in this case).

# Bar graph for categorical variable

gradebook %>%

# Code defining the

mutate(letter_grade =

factor(letter_grade, levels = c("A+",

"A",

"A-",

"B+",

"B",

"B-",

"C+"))) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = letter_grade,

fill = running_average > 90)) +

geom_bar() +

labs(title = "Bar Graph of Student Grades",

x = "Letter Grades",

y = "Count",

fill = "A or Better") +

scale_fill_dataedu() +

theme_dataedu()

Figure 8.1: Bar Graph of Student Grades

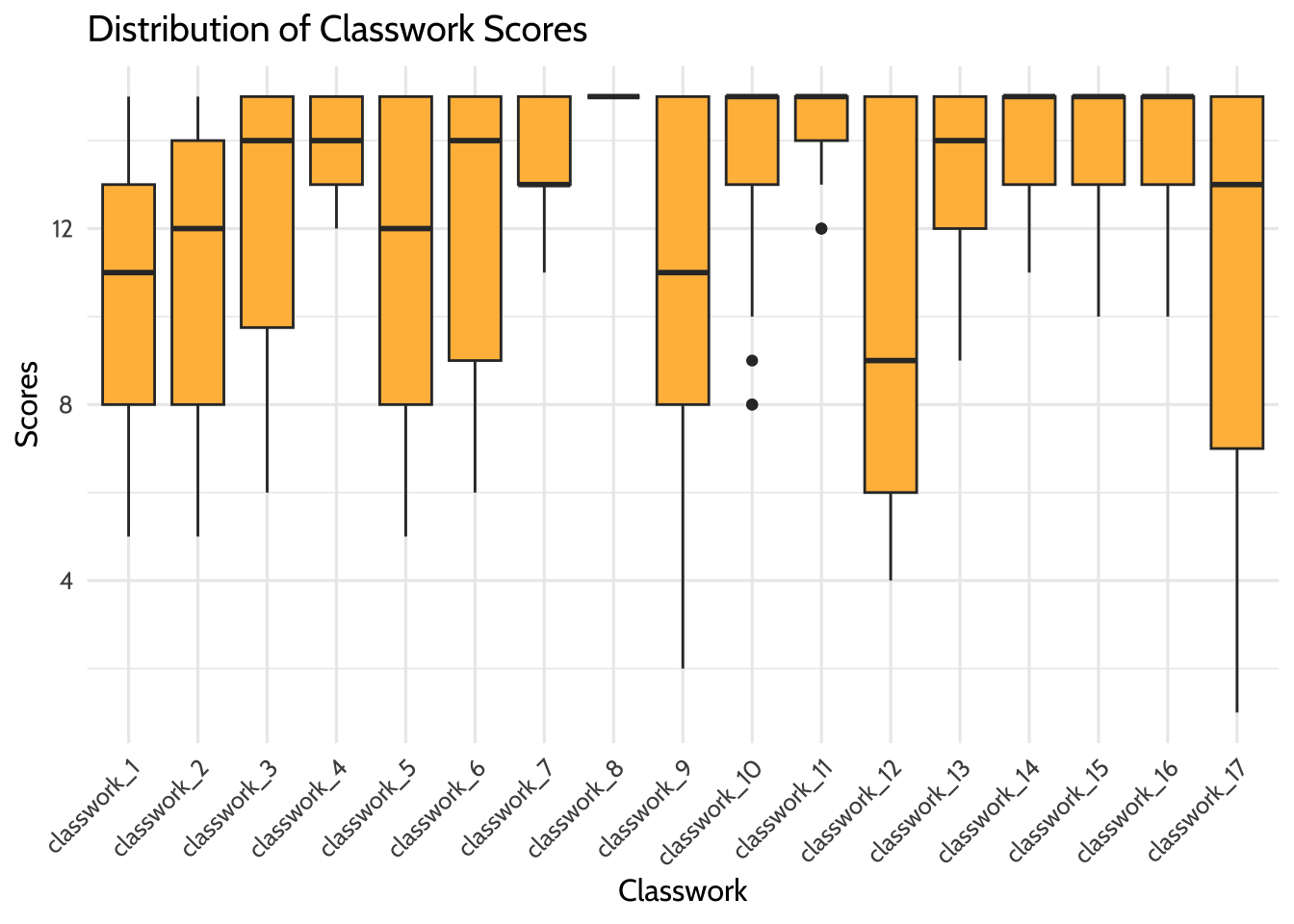

Using {ggplot2}, you can create many types of graphs. Using classwork_df from earlier, you can see the distribution of scores and how they differ across classwork assignments using box plots. This is possible because of the way you cleaned the classworks and scores variables earlier in this walkthrough. As in the last plot, you can change the factor levels of classwork_number so they are in an understandable order.

# Box plot of continuous variable

classwork_df %>%

mutate(classwork_number =

factor(classwork_number, levels = c("classwork_1",

"classwork_2",

"classwork_3",

"classwork_4",

"classwork_5",

"classwork_6",

"classwork_7",

"classwork_8",

"classwork_9",

"classwork_10",

"classwork_11",

"classwork_12",

"classwork_13",

"classwork_14",

"classwork_15",

"classwork_16",

"classwork_17"))) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = classwork_number,

y = score,

fill = classwork_number)) +

geom_boxplot(fill = dataedu_colors("yellow")) +

labs(title = "Distribution of Classwork Scores",

x = "Classwork",

y = "Scores") +

theme_dataedu() +

theme(

# removes legend

legend.position = "none",

# angles the x axis labels

axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 45, hjust = 1)

)

Figure 8.2: Distribution of Classwork Scores

8.8.2 Model data

8.8.2.1 Deciding on an analysis

When you explore datasets, it’s useful to identify hypotheses that you can test in the data through a model. For example, you can ask the question “Can we predict overall grade using formative assessment scores?” Then, you can use a model to explore the relationship between the response variable Y (overall grade) and a predictor variable X (formative assessment scores). The goal of this model is to create a mathematical equation that describes the relationship between overall grade and formative assessment scores when only formative assessment scores are known.

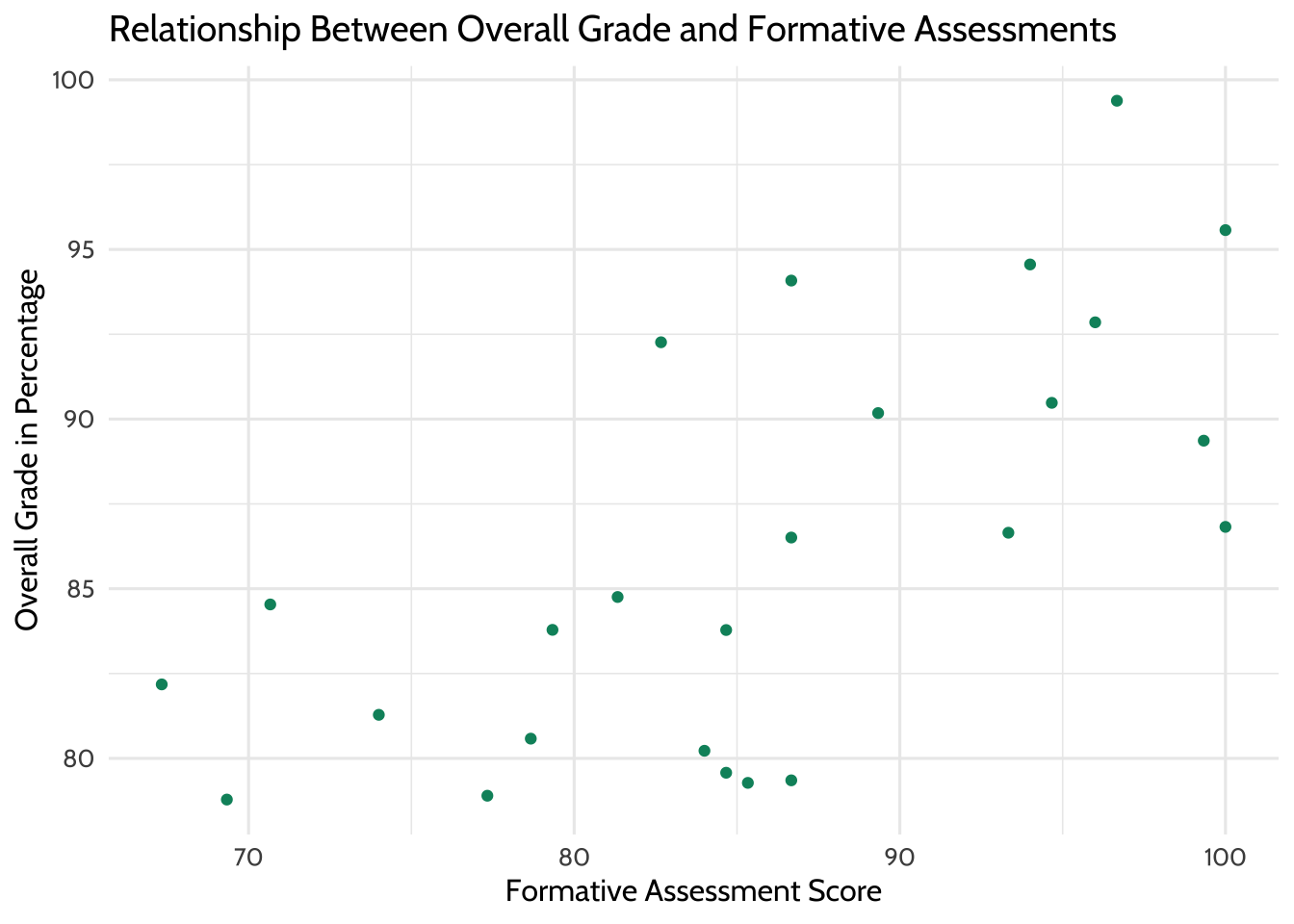

8.8.2.2 Visualize data to check assumptions

Before building a model, it’s important to visualize the underlying data to see distributions, trends, or patterns. Different models operate under assumptions about the structure of the underlying data. Exploring these assumptions ahead of time will empower you to explain the model better after the analysis is complete. You’ll be using {ggplot2} to explore these assumptions.

8.8.2.3 Linearity

A linear regression model assumes that variables in the underlying data have a linear relationship. You’ll explore this assumption by plotting the formative assessment scores and the overall grades.

# Scatter plot between formative assessment and grades by percent

# To determine linear relationship

gradebook %>%

ggplot(aes(x = formative_assessments,

y = running_average)) +

geom_point(color = dataedu_colors("green")) +

labs(title = "Relationship Between Overall Grade and Formative Assessments",

x = "Formative Assessment Score",

y = "Overall Grade in Percentage") +

theme_dataedu()

Figure 8.3: Relationship Between Overall Grade and Formative Assessments

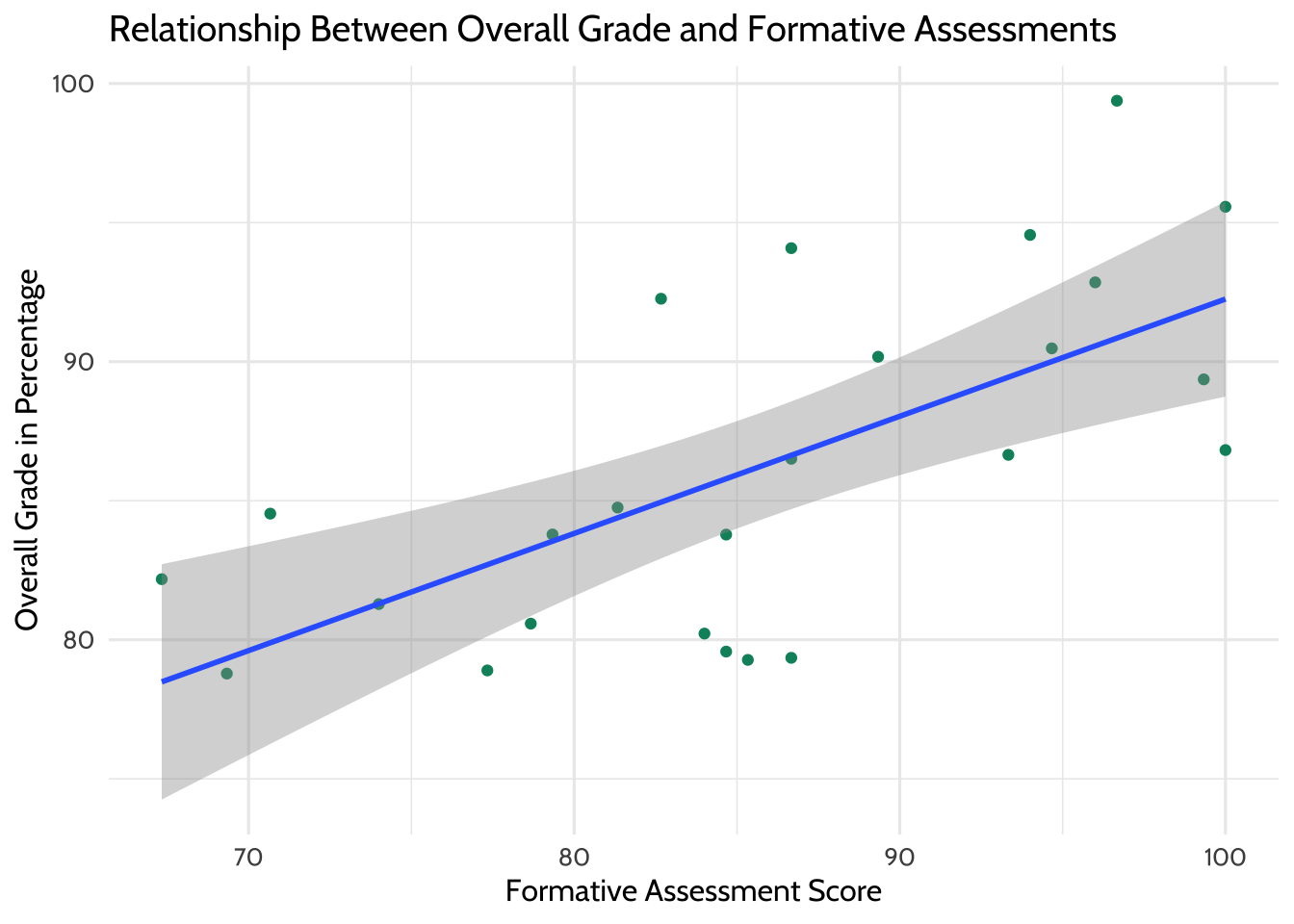

The graph suggests a correlation between overall class grade and formative assessment scores. As the formative scores goes up, so does the overall grade. To see this better, use {ggplot2} to add a line of best fit.

# Scatter plot between formative assessment and grades by percent

# To determine linear relationship

# With line of best fit

gradebook %>%

ggplot(aes(x = formative_assessments,

y = running_average)) +

geom_point(color = dataedu_colors("green")) +

geom_smooth(method = "lm",

se = TRUE) +

labs(title = "Relationship Between Overall Grade and Formative Assessments",

x = "Formative Assessment Score",

y = "Overall Grade in Percentage") +

theme_dataedu()

Figure 8.4: Relationship Between Overall Grade and Formative Assessments (with Line of Best Fit)

8.8.2.4 Outliers

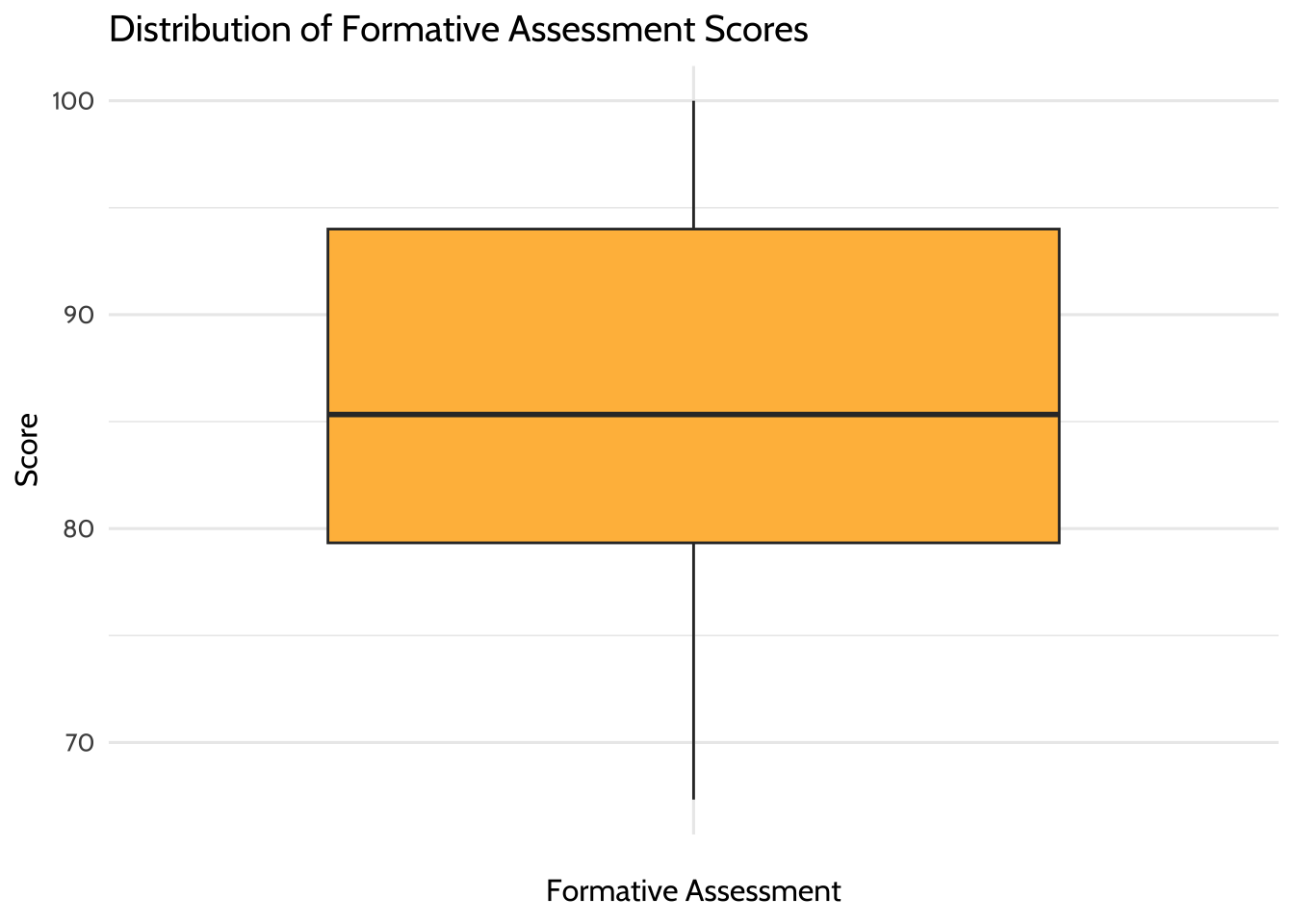

The usefulness of a model also assumes that outliers in the data do not have a large influence on the model. You’ll explore this assumption by creating box plots for each of the variables you are modeling.

The first box plot is for the formative assessment scores:

# Box plot of formative assessment scores

# To determine if there are any outliers

gradebook %>%

ggplot(aes(x = "",

y = formative_assessments)) +

geom_boxplot(fill = dataedu_colors("yellow")) +

labs(title = "Distribution of Formative Assessment Scores",

x = "Formative Assessment",

y = "Score") +

theme_dataedu()

Figure 8.5: Distribution of Formative Assessment Scores

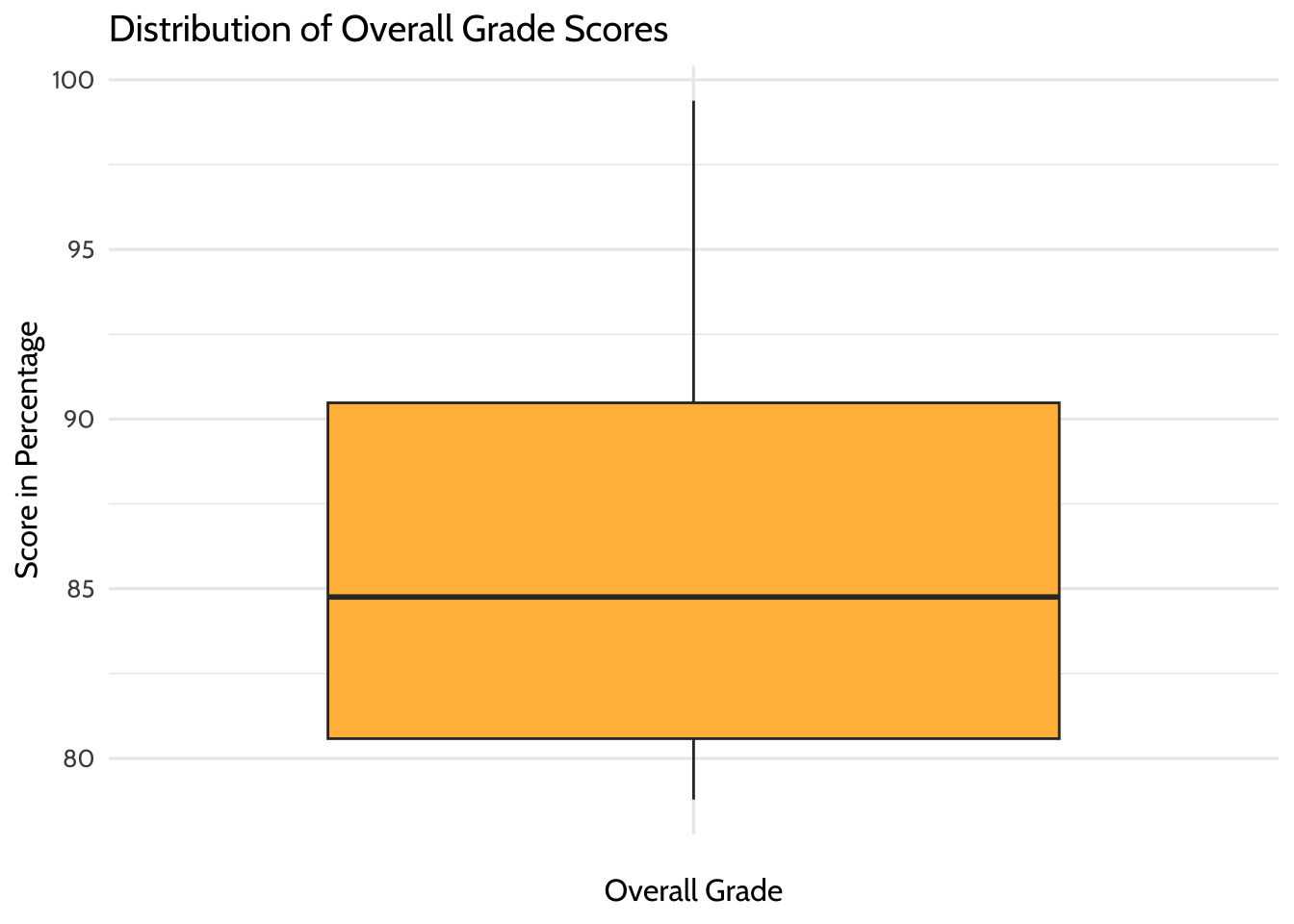

The next box plot is for the overall grade scores:

# Box plot of overall grade scores in percentage

# To determine if there are any outliers

gradebook %>%

ggplot(aes(x = "",

y = running_average)) +

geom_boxplot(fill = dataedu_colors("yellow")) +

labs(title = "Distribution of Overall Grade Scores",

x = "Overall Grade",

y = "Score in Percentage") +

theme_dataedu()

Figure 8.6: Distribution of Overall Grade Scores

Based on these plots, there doesn’t seem to be outliers in either of these variables.

8.8.3 Correlation analysis

The usefulness of a model also assumes a relationship between the variables in the underlying data. You’ll explore this assumption by computing the correlation coefficient between the formative assessments and overall grades.

## [1] 0.663Correlation coefficients go from –1 to 1. If one variable increases with the increasing value of the other, then they have a positive correlation (towards 1). If one variable decreases with the increasing value of the other, then they have a negative correlation (towards –1). If the correlation coefficient is 0, then there is no relationship between the two variables.

Correlation is useful for finding relationships but it does not imply that one variable causes the other. Correlation does not necessarily mean causation.

8.9 Results

In Chapter 7, you learned about linear models. You’ll use that same technique here. Now that you’ve checked your assumptions and seen a linear relationship, it’s time to build the linear model. This will be a mathematical formula that calculates your running average as a function of your formative assessment score. You’ll again use the lm() function, where the arguments are:

- Your predictor (

formative_assessments) - Your response (

running_average) - The data (

gradebook)

lm() is available in “base R”—that is, you won’t need to install additional packages.

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = running_average ~ formative_assessments, data = gradebook)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -7.281 -2.793 -0.013 3.318 8.535

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 50.1151 8.5477 5.86 5.6e-06 ***

## formative_assessments 0.4214 0.0991 4.25 3e-04 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 4.66 on 23 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.44, Adjusted R-squared: 0.416

## F-statistic: 18.1 on 1 and 23 DF, p-value: 0.000302When you fit a model to two variables, you create an equation that describes the average relationship between them. This equation uses the (Intercept), which is 50.11511, and the coefficient for formative_assessments, which is 0.42136. The equation reads like this:

running_average = 50.11511 + 0.42136*formative_assessmentsYou can interpret these results by saying, “For every one unit increase in formative assessment scores, we can expect a 0.421 unit increase in running average scores”. This equation estimates the relationship between formative assessment scores and running average scores in the student population. Think of it as an educated guess about any one particular student’s running average, if all you had was their formative assessment scores.

8.9.1 More on interpreting models

Challenge yourself to apply your education knowledge to the way you share about your model’s output. In particular, note that statistical models describe what happens in general, but cannot fully capture what happens on a case by case basis.

To illustrate this concept, consider predicting how long it takes for you to run around the block. Imagine you ran around the block five times and after each lap you recorded your time. After the fifth lap, see that your average lap time is five minutes.

If you were to guess how long your sixth lap would take, you’d be smart to guess five minutes. But intuitively you know there’s no guarantee the sixth lap time will land right on your average. Maybe you’ll trip on a crack in the sidewalk and lose a few seconds, or maybe your favorite song pops into your head and gives you a 30-second advantage.

Statisticians call the difference between your predicted lap time and your actual lap time a “residual” value. Residuals are the differences between predicted values and actual values that aren’t explained by your linear model equation.

If you were describing the formative assessment system to stakeholders, you might say something like, “We can generally expect our students to show a 0.421 increase in their running average score for every one point increase in their formative assessment scores”. That makes sense because your goal is to explain what happens in general.

But you can rarely expect every prediction about individual students to be correct, even with a reliable model. So when using this equation to inform how you support an individual student, it’s important to consider the real-life factors, visible and invisible, that influence an individual student’s outcome.

It takes practice to interpret and communicate model results well. Start by exploring model outputs in two contexts: first, as a general description of a population and second, as a practical tool for helping individual student performance. When you’re ready to share with colleagues, consider sharing the results as a written report. You can do this through tools like R Markdown (https://rmarkdown.rstudio.com/). Tools like this empower you to generate reports that include text, code, and code output in a single document.

8.10 Conclusion

This walkthrough followed the basic steps of a data analysis project. You imported the data, cleaned it, and transformed it. Once you had the data in a tidy format, you explored it through data visualizations. And finally, you modeled the data using linear regression.

You will continue to explore analyses and statistical modeling in later chapters (i.e., Chapter 9 on aggregate data, Chapter 10 on longitudinal analyses, Chapter 13 on multi-level models, and Chapter 14 on random forest machine learning models).